Plus, many Design Community sessions were relegated to rooms that were too small to accommodate their audiences. Not only were design-centered courses full, there were long waiting lists of people hoping to get into them, while sessions for other communities, in larger rooms, were sometimes sparsely attended. I spoke with several attendees who were as frustrated by the limited options for designers as I was. Not only were designers unable to get into the courses of their choice, because their registrations were full, they couldn’t switch courses if they weren’t enjoying a course they were in.

I attended the Design Community SIG, on Wednesday, May 2, during which Elizabeth Dykstra-Erickson told me that design-focused content will be even more limited next year at CHI 2008, in Florence (Firenze), Italy. Elizabeth and Jonathan Arnowitz are the Design Community Co-Chairs for CHI 2008, but the Conference Committee dictates the number of Design Community sessions. The SIGCHI leadership also enforces the same paper-selection process that, while appropriate for academics, is not an effective means of selecting content for the Design Community. It’s discouraging that such passionate advocates for the Design Community as John Kolko, Bill Lucas, Elizabeth Dykstra-Erickson, and Jonathan Arnowitz have met with such limited success in bringing design content to CHI.

CHI 2007 did a better job of serving the UX Management Community, which focuses on “the business and organizational aspects of HCI.” (Though HCI is the wrong term. Nobody outside of academia or research uses that term.) Perhaps the Management Community was better served because it is the source of much of the funding for the conference.

The conference also did a good job of serving user research and usability professionals through its Usability Community. I can’t help wondering whether the establishment of the Usability Professionals’ Association and its popular conference brought home to CHI the need to better serve this community. Will it be necessary to establish an association for UX design professionals and a conference that successfully competes with the CHI conference to awaken CHI to the need to adequately serve the design community?

The organizers of CHI 2007 invited us to: “Join us as we reflect on our amazing accomplishments over the past 25 years while we look forward to those we haven’t yet tried to imagine.” Perhaps it’s difficult to reach beyond and look back at the same time. Still the conference had some high points, which I’ll share with you when I describe its content and presenters.

Organization

In many respects, CHI 2007 was a well-organized conference. With 25 years of experience putting on conferences, CHI knows how to make a conference run smoothly. Audio, video, and lighting were superb. CHI also provided a lot of services to make attendees’ days at the conference easier, including wireless high-speed Internet access and a press room. Friendly volunteers were always available to help.

Two days of workshops, on Saturday, April 27, and Sunday, April 28, preceded the main conference. However, “only those who have had position papers accepted can attend workshops.” I did not choose to attend any workshops.

Over the four full days of the conference, CHI offered fourteen tracks of sessions, running in parallel. Admittedly, that’s a lot of sessions to manage, especially with this year’s unusually high attendance. However, the allocation of rooms to sessions was poorly thought out. As I described earlier, there were overflow crowds for some sessions, while attendance for others was sparse—at least in relation to the size of the rooms in which they took place. For some sessions, overflow crowds were able to watch on monitors that were placed in the hallways. (Unfortunately, this sometimes made the hallways impassable.) However, no monitors were provided for the sessions I regretted missing.

During registration for future conferences, I suggest that the organizers of CHI poll attendees about their needs and preferences. For example, they might ask:

- Are you an academic, student, or UX professional?

- What is your area of specialty? (Provide check boxes appropriate to the category an attendee selected in the previous question.)

- In what communities of interest are you likely to attend sessions? Design? Education? Engineering? Management? Research? Usability?

- What kinds of sessions are you likely to attend? Courses? Experience reports? SIGs? Interactive sessions? ALT.CHI sessions? Papers? Competitions?

- Of all the sessions in the conference program, which are you most likely to attend? (Initially, provide check boxes for sessions in each category an attendee selected in the previous question, but let attendees choose sessions in other categories, too.)

Gathering this information in advance would give the organizers some idea about the demand for space in particular sessions and ensure that people wouldn’t be shut out of the sessions they wanted to attend.

Content & Presenters

The majority of the worthy content for UX professionals comprises courses. Attending CHI on a press pass, I wasn’t permitted to sign up for courses in advance. Therefore, I was unable to get into the courses I’d planned to attend. I can’t review what I didn’t experience, so this part of my review will be relatively brief. Last year in Montréal, I had spent most of my time in courses. The rooms there were larger, so I was able to get into whatever courses I wanted to attend.

The upshot of my CHI 2007 experience is that, unless the CHI organizers permit members of the press to sign up for courses in advance or otherwise ensure access to them, I doubt I’ll review CHI again. It was bad enough to find myself in San Jose with nothing to do at the conference, but if I had incurred the expense of a flight and hotel accommodation in some remote place rather than simply driven in from my home in the Santa Cruz mountains, I would have been seriously displeased. Without knowing I’d have access to content that would be of interest to UXmatters readers, investing in a trip to another city or country isn’t a risk I’d undertake. Of course, I do hope CHI finds a solution to this problem.

In most cases, I’ll review only what were for me the highlights of the conference. Unfortunately, there were many hours when there just weren’t any really interesting sessions other than courses.

Day 1: An Evening of Courses

Unusually, the conference began on a Sunday evening, April 28, with four courses:

- Human-Computer Interaction: Introduction and Overview

- An Introduction to Computer-Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW)

- HCI History: Trajectories into the Future

- Drawing Ideas: Visualization and Design Sketching

Day 2: Opening Plenary: Reaching for the Intuitive

Presenter: Bill Moggridge

Day 2 of the conference began strongly with Bill Moggridge’s opening plenary, “Reaching for the Intuitive.” Shown in Figure 1, Moggridge is a renowned industrial designer, co-founder of IDEO, and author of Designing Interactions. In a time when most organizations are emphasizing user-centered design methodologies over intuitive design and incremental improvement over innovation—despite all the talk one hears about innovation these days—I think the design community needed to hear what he had to say. I really enjoyed his presentation.

Moggridge opened his talk by saying, “After 25 years, we should all be ready to congratulate ourselves for the progress we’ve made. Perhaps it’s time to embrace the more qualitative, intuitive aspects of design—to harness the subconscious aspects of design. Why intuitive design?

- “The problems are getting more complex.

- “Technology is part of our everyday lives—not just work. It’s now in every part of our lives.

“Now, we have to design interactivity.” Moggridge gave the example of the NTT DoCoMo i-mode mobile Internet service in Japan, which he told us has 32 million subscribers. He said, “The user interface of the phones should be easy enough for everybody. The hierarchy of complexity, in terms of the design problem, requires making decisions quickly, without having to justify them—experimentation.” Moggridge showed us a woman struggling to order a drink from a vending machine using i-mode. It took her 35 minutes to successfully order her drink, because of a variety of usability problems she encountered. People from different parts of the world use mobile phones differently. “The way people use phones is diametrically opposite.” For example, in Japan, people send text messages, because they consider it rude to talk on mobile phones in public places. In the USA, people spend a lot of time driving and prefer to use their phones to talk with one another.

Moggridge told us, “Designing something that’s aesthetically satisfying becomes more important as time moves on.” He spoke about venture capitalist David Liddle’s “three stages of adoption” for new technology products. First, enthusiasts adopt a new technology. Such people appreciate a technology for what it is and don’t care about ease of use or cost. “The fact that it may be difficult to use actually adds to the fun,” said Moggridge. Next, business users adopt the technology. During this stage, people realize they can use the technology to help them accomplish their work. Ease of use becomes more important, because business users care about the productivity they can achieve using the technology. Finally, as the technology’s volume of sales becomes big enough, it reaches a price point that is affordable for consumers. At the consumer stage, “style and intuitive design” become paramount. “These stages have profound implications for interaction design, as the design process changes with each phase to meet the increasingly practical needs of each new set of users.”

“How can we harness intuition? By understanding design and design thinking and developing design skills,” said Moggridge. Charles Eames once defined design as “a plan for arranging elements in such a way as to best accomplish a particular purpose.”

Moggridge used the analogy of an iceberg to show the relationship between the conscious mind and the subconscious. The conscious mind is like the tip of an iceberg that is visible above the water, while the subconscious mind is like the larger mass of the iceberg that lies submerged and hidden beneath the surface of the water.

According to Moggridge, “Design thinking harnesses design skills

- “to frame or reframe a problem and objectively figure out what the brief is really

- “to envision and create alternatives

- “to select from among the alternatives, however they’re generated, knowing intuitively how to choose the best approach”

- “to visualize and prototype the intended solution in order to see what works quickly, in each iteration

- “to synthesize a solution from all of the relevant constraints, understanding everything that will make a difference to the result.”

Throughout his talk, Moggridge cited examples of design innovation from his book, Designing Interactions. Intuitive design is the hallmark of that work:

- Jeff Hawkins’s design for the PalmPilot—He had four design criteria—size, price, synchronization, and speed. It had to be fast.

- Tim Mott’s desktop metaphor—He developed the metaphor for the Xerox PARC On Line Office System.

- Larry Tesler and Bill Atkinson’s design for the Apple Lisa operating system—They developed a prototype every day, by brainstorming user interface design ideas, then each of them coding 12 hours a day. Larry was the day shift; Bill, the night shift. Larry’s goal was no modes, so he wanted to avoid the kind of hierarchical menu-driven interface in which users couldn’t see all levels in the hierarchy at once, making people keep track of the hierarchies in their heads. So, in one night, Bill came up with the design for drop-down menus, which were easily scanned, used highlighting to show selection, and provided keyboard shortcuts. “He thought of all that in one night,” said Moggridge.

- Mat Hunter’s interaction architecture for digital photography—To help Kodak make the transition from film to digital photography, he created this architecture and developed a UX prototype that let users capture, review, share, and delete images.

- Paul Mercer’s toolkit for the iPod—He did not design the iPod, but provided the building blocks for it.

“We now need people with a subjective, empathic approach to design. Intuition is an important moment of crystallization, but based on all the work that’s gone before,” said Moggridge. “Like most things in life, you can do design well or poorly. It’s about having the knowledge and understanding which alternative is best. Education is learning by doing—trying things—allowing the subconscious mind to inform intuitions that guide actions. You do just trust your doing of it. Design has now reached a stage at which Ph.D’s, who understand how design works, differentiate between designing user interfaces or objects and services, which have a social aspect. Both industry and designers have failed at making these things as simple as they can be. Perhaps we’ll see more development for specific purposes. General-purpose tools are the enemy of simplicity. Designers must know the state of the art—best practices—if they’re designing a product that isn’t unique, but when designing with no precedent, they must use intuition. Design is spreading its influence—through business as well.”

CHI madness followed the opening plenary. For attendees who are interested in papers sessions, there’s no better way of getting their flavor. Since I’m generally not interested in seeing papers presented, I wish CHI would include other types of sessions in the CHI madness as well.

Day 2: Bill Moggridge Interview

The organizers of CHI 2007 arranged some special events for members of the press, including an opportunity to interview Bill Moggridge. Here are some of the thoughts he expressed during the interview:

- The trend is to move the person into the environment—with PDAs, wearable computers—into buildings, the architecture, the car.

- Well-designed interfaces don’t get in the way. You can learn a lot from games.

- People don’t give due respect to the part of the iceberg that’s submerged.

- It’s difficult to justify or quantify intuitive design.

- A designer gets a great idea; prototypes and tests it. When doing iterative design, inform each attempt with intuition.

- People think of research as understanding ideas.

- You build an innovation process, developing tacit knowledge, but if you don’t think, you get stuck in the process. You must be able to adapt to change. You must understand how design works.

- Cars are a very mature interface. Thirty percent of it’s computer science. There’s an enormous amount of computer intelligence in the car. It gives you computation when you need it.

- Heads-up displays are dangerously distracting for drivers. Anything that’s a tiny bit distracting takes away from the ability to focus on driving and is very dangerous.

Day 2: Who Killed Design? Addressing Design Through an Interdisciplinary Investigation

Moderators: Scott Pobiner and Anijo Mathew

Panelists: Bill Moggridge, Bill Buxton, Terry Winograd, and Meg Armstrong

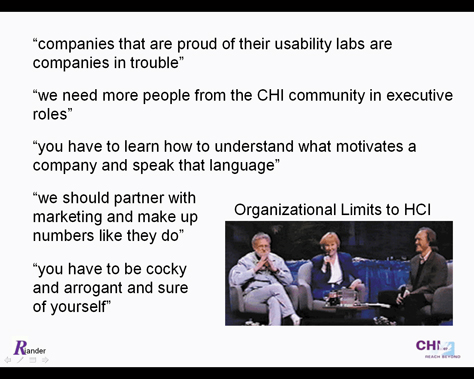

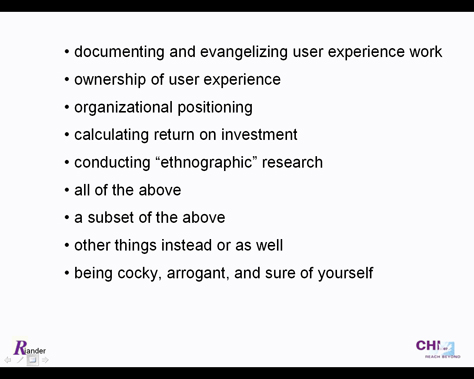

The interactive session “Who Killed Design?” took an interdisciplinary look at design, encompassing viewpoints from both industry and academia. Here’s the lineup of panelists (shown in Figures 2 and 3):

- Bill Moggridge—An award-winning industrial designer who designed the first laptop computer—the GRiD Compass—and co-founder of IDEO—a company whose name is synonymous with innovation—Moggridge pioneered interaction design as a discipline. Formerly, Visiting Professor in Interaction Design at the Royal College of Art in London, he is currently an Associate Professor in the design program at Stanford University. The MIT Press recently published his book Designing Interactions.

- Bill Buxton—Currently Principal Researcher at Microsoft, Buxton has balanced design with pure and applied research throughout his career. He is now an Associate Professor in the Department of Computer Science at the University of Toronto. Buxton has served as editor for numerous HCI books. His new book on sketching and interaction design, Sketching User Interfaces: Getting the Design Right and the Right Design, launched at CHI 2007.

- Terry Winograd—Professor of Computer Science, Director of the Human Computer Interaction Program, and co-founder of the d.school, or Institute of Design, at Stanford University, Winograd is the author of several books, including Understanding Computers and Cognition, with Fernando Flores, Usability: Turning Technologies into Tools, with Paul Adler, and Bringing Design to Software. In collaboration with David Kelley, Winograd teaches Interdisciplinary Interaction Design at Stanford.

- Meg Armstrong—Currently, Associate Professor and Chair, Department of Design and Management, at Parsons, the New School for Design, Armstrong specializes in cultural theory and the application of qualitative design research to product development and innovation. She was formerly Director of User Experience Research for Sapient.

Unfortunately, I was detained in the press room, so missed the first part of this session, but here’s some of the dialogue on “who killed design”:

- Bill Moggridge—“It’s not close to death. It’s been around long enough to do some interesting things, but it’s not really grown up yet. We have a lot of learning to do before we grow up. … Prima donna designers are giving way to multidisciplinary teams. … Adobe buys innovation rather than growing it internally. … Designers commit suicide when they say, ‘I’ve got this great idea. Just trust me.’ … You build your reputation. Until we start to understand and respect that….”

- Bill Buxton—“I want the world’s best industrial designers in C-level and all other roles. The renaissance man is over, but long live the renaissance team. How do we get the renaissance team? … Business schools don’t teach collaboration. It’s cheating. They’re maintaining the silos. … It’s not about the world of design. It’s about the design of the world.”

- Meg Armstrong—“Practice-based learning [is important]. Even identifying a problem is hard for a lot of people—problem setting instead of problem solving.”

- Bill Moggridge—“At IDEO, we’ve been practicing this interdisciplinary approach. … The people who are most successful are T-shaped people, who have one deep specialty and broad knowledge. What you need for team success is this collection of T-shaped people. Just respect each other. It’s always interesting to compare the need for creative leadership with the need for collaboration. Set a strong direction and stick to it.”

- Terry Winograd—“Engineers love to fix things. What can I connect that to?”

- Bill Moggridge—“What happens with open source design? That’s much more confusing.”

- Bill Buxton—“Let’s stop talking about open source like it’s religion.”

- Bill Moggridge—“There’s a huge difference between design and innovation. One of the biggest differences is trying to invent some new possibility. For innovation, if you really have no idea what it’s going to be, you have to use different methods.”

- Bill Buxton—“Design isn’t art. In Europe, engineering is called product design.”

- Terry Winograd—“Design is about trade-offs. Sometimes giving design less time helps, because designers don’t overthink it.”

- Meg Armstrong—“Time constrains innovation.”

- Bill Buxton—“One of the myths perpetrated about design is the flash of genius. You don’t expect every design to be Wayne Geary. What I want is good journeyman designers who can crank it out every day.”

For more dialogue![]() on this interesting topic, visit the Who Killed Design? Web site.

on this interesting topic, visit the Who Killed Design? Web site.

Day 3: “Get Real!” What’s Wrong With HCI Prototyping and How Can We Fix It?

Moderator: William Jones

Panelists: Victoria Bellotti, Mary Czerwinski, Jonathan Grudin, Tom Rodden, and Jared Spool

I really like the format of the interactive sessions at CHI, because they are truly interactive discussions—often on controversial topics. However, this interactive session didn’t live up to its description in the conference program, which promised a discussion of prototyping. “A prototype—as a means to evaluate and communicate a good idea—is often an essential step toward useful, shipping products and also toward a deeper understanding of what people really need.” Initially, I thought I might have landed in the wrong session. It was an uneasy amalgam of discussion about paper submission—I never did figure out what that had to do with prototyping—and user evaluation—not the creation—of prototypes. But there were some good people on the panel (shown in Figure 4), so I decided to slog through the very dull paper-submission detours in the hope of finding something interesting and was rewarded with some very lively discussion. I’ll report only the interesting bits. Figure 4 shows the panel.

The first nugget came from Jonathan Grudin of Microsoft who told us, “Overwhelmingly, prototype evaluations are done by friends of the prototype builders. They like the builders, so they want to say nice things. Later, you realize the product never made it into the marketplace. We never see a paper on why it failed. You see reports in the literature that are very promising and lead others down the same path. … Another problem I see today, there’s such a proliferation of products coming out.” Prototype builders suggest, “‘You evaluate my prototype, and I’ll evaluate yours.’ We shouldn’t evaluate our own prototypes.”

Victoria Bellotti of PARC asked, “What do we build prototypes for? Understandability, intuitiveness, usability, accessibility, efficiency, safety, usefulness. They improve some aspect of life.”

Mary Czerwinski, also of Microsoft, lamented, “In the visual information space, there are very few prototyping tools. So it’s a very costly enterprise. These prototypes require a lot of interesting transitions, which are costly things to prototype. You can’t really prototype these things very well—dynamic animations, transparency, rotations, translations, zooming, and so on. Users have to buy into your prototypes, so they’re willing to drop their daily tools. I don’t see a really good way around this—except some toolkits for information visualization.”

Not unexpectedly, the real gem came from Jared Spool, who began, “I want to take a different tack and talk about the importance of failure. So, I want to talk about me.” Jared proceeded to tell us the history of his early career before UIE, which constituted a litany of failure. He was fired from his first two jobs, then experienced problems working for some companies that failed. “And I learned from that” was Jared’s refrain. He worked for a company that went bankrupt. He got laid off. He was fired for a dress-code violation. “I learned from my own experience and started my own company, because I couldn’t hold a day job. So, failure turns out to be a really important thing that we learn from all the time. Apple has had a tremendous number of failures—the Lisa, the Newton.” There have been a lot of failures in the technology industry—Altavista, tablet PCs, Friendster. It’s important we talk about failure, so I want to talk about morbidity and mortality.” Jared’s monologue was one of the highlights of CHI for me. As always, he made me smile. Later, he said, “My position is comic relief.” Yes, indeed, and much more.

Then, Tom Rodden got on the failure bandwagon, saying, “We don’t celebrate failure enough.” He was absolutely right, of course, because without taking risks, there is no innovation, but when you take risks, you sometimes will fail. Tom brought the discussion back to prototypes by saying, “A prototype is the road to a product. Prototypes should support research.”

Victoria asked, “How many people think text-editing tools don’t need improvement? Software is simply appalling. Why aren’t people trying to improve things?” I heartily concur.

About prototyping, Jared said, “We don’t have platforms that let us prototype just one feature within an existing system.” To which Tom replied, “Open source. People are putting their toolkits out there.”

Jared told us, “We have clients that bring us multiple prototypes—three variants based on the same misconceptions. We dissect the failures and go from there.” Tom replied, “Instead of using words like success and failure, you should use other words like learning.” Jared came right back with, “I don’t think you learn anything from success. It’s when you fail that you can pinpoint problems, and that’s where learning comes from.” Victoria admitted, “I’ve never built a prototype that was entirely successful.” Then, Jonathan said, “But we aren’t getting reports on failures. It’s something we have to deal with.” Mary replied, “Sometimes the experimenter is very biased. You have to be aware of that and allow for it.” Tom asked, “If you haven’t had enough failure, have you been risking enough?”

Jared mentioned Apollo and frameworks and APIs that “let us build on top of other things. This kind of thinking is now prevalent.” Victoria replied, “It’s extremely difficult to build add-ons to existing software.”

Tom stated, “It isn’t that easy to identify success and failure.” Jared quipped, “In theory, theory and practice are the same, but in practice, they almost never are. Having a way to go back and look at what has and hasn’t worked is very useful.”

Mary said, “With the introduction of toolkits and programmability in software, I’m optimistic that prototyping will improve.” Victoria told us, “I’m very worried that people will become invested in their skills of using software. I’m very concerned that things being designed in a non-ideal way will continue.”

Jonathan concluded, “Now, there are better tools for prototyping, and the difference between prototypes and products is going away. You can put a beta up and get feedback very easily. The necessity for innovation is going away. There’s a greater need to evaluate what people are doing with what’s out there.”