Aspirin Help should immediately alleviate the, hopefully, short-term pain of an acute problem. Problems in need of Aspirin Help represent clear diversions from customers’ desired tasks and usually arise when customers are completely stuck and looking for an immediate fix to their problems.

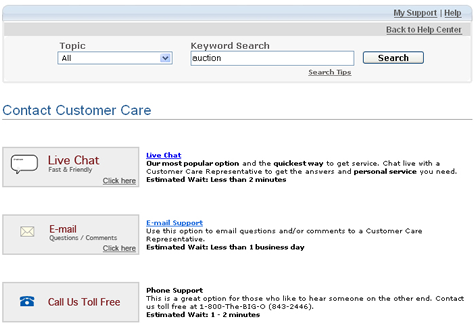

A customer’s mindset when looking for such content is that of fear—for example, a fear of losing money, losing time, or feeling stupid. The natural response to such fear is usually anger and frustration, a highly emotional state, and Aspirin Help solutions need to take the customer’s complex emotional state into account. Aspirin Help content must present a straightforward and simple way to address the customer’s immediate problem, as shown in Figure 1.

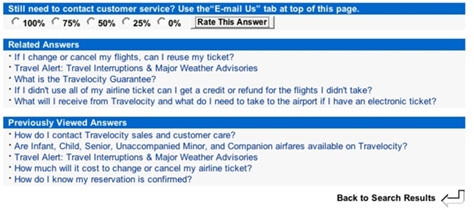

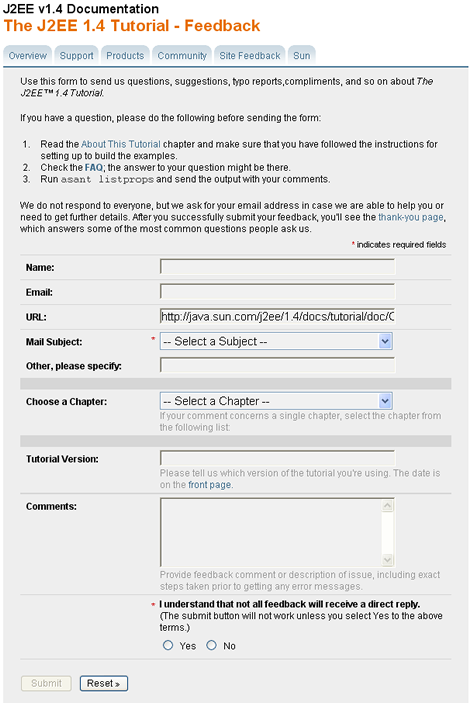

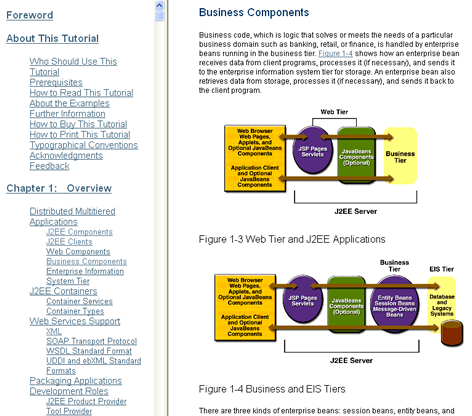

Unlike Aspirin Help solutions that offer immediate fixes, Vitamin Help solutions maximize user effectiveness on a Web site. Vitamins are preventative in nature. You need to take them in advance. So customers need to read Vitamin Help before performing tasks and interactions for it to be effective. Generally, Vitamin Help comes in the form of tutorials and articles that you expect customers to review with a calmer mindset, when seeking opportunities for gradual learning with the goal of obtaining beneficial long-term knowledge and skills. As Figure 2 shows, Vitamin Help solutions can be much more sophisticated, taking the form of interactive multipage tutorials or video presentations.

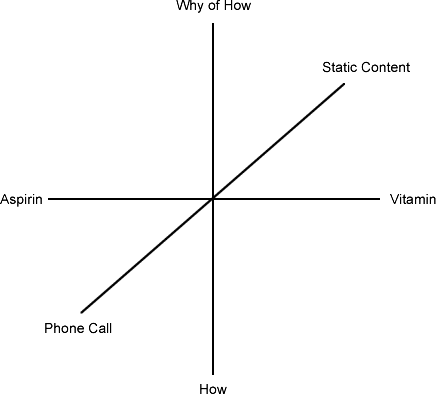

Given these different and distinct uses for Help content, it is beneficial to classify Help content using the following three attributes:

- immediacy—Aspirin Help versus Vitamin Help

- depth of knowledge—how versus the why of how

- touch—static content versus a phone call

Each axis in Figure 3 represents one of the attributes we can use to evaluate each component of a Help system to determine whether it is appropriate to the task, the existing level of customer knowledge, the task’s level of complexity, and the sensitivity of the issue.

When evaluating the appropriateness of Help content to each specific use case, it is important to consider where your content falls along each of these attribute axes.

Stick to Established Best Practices

People expect to find Help even faster and easier than they can find your merchandise or content, so in most cases, it is safest to stick with the established mental models and design practices for Web site user assistance. People often have a strong mental model for how Help systems should work. Deviating from that mental model and forcing people to think harder when they are already confused is likely to lead to anger and frustration. Most examples of good Web site user assistance follow a similar design, often including the following components:

- proactive inline Help

- a single Help landing page

- navigation that is optimized for browsing rather than keyword search

- complete Help solutions through multiple landing pages

On the best Web sites, these components work together to provide effective user assistance.

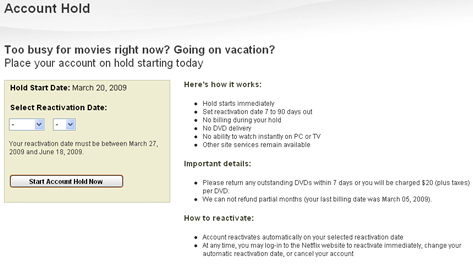

Proactive Inline Help

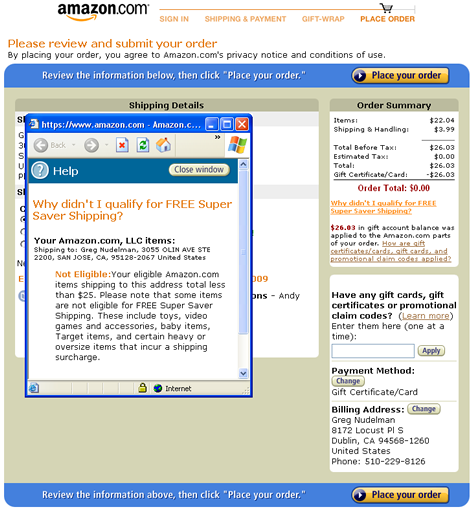

Inline Help provides the first line of defense against customer frustration by proactively offering both Aspirin and Vitamin Help content where you know your customers are most likely to need it. Inline Help is part of the site’s integral functionality. Where necessary, it is more extensive, but may be absent entirely where functionality is familiar or easy to understand. Figure 4 shows the excellent inline Help Netflix provides to help customers put an account on hold. There is enough information embedded on the page to enable confident on-the-spot decision making. There’s no need to navigate anywhere else for more information. It even explains how to reactivate the account later on.

Good inline Help is preferable to all other types of Help, because customer expectations for inline Help are low. Inline Help often delights customers, because of the care and attention a company has invested in placing the right Help where customers need it most. People usually perceive inline Help as easy to follow and, in most cases, it can painlessly take care of 90% of customers’ need for assistance.

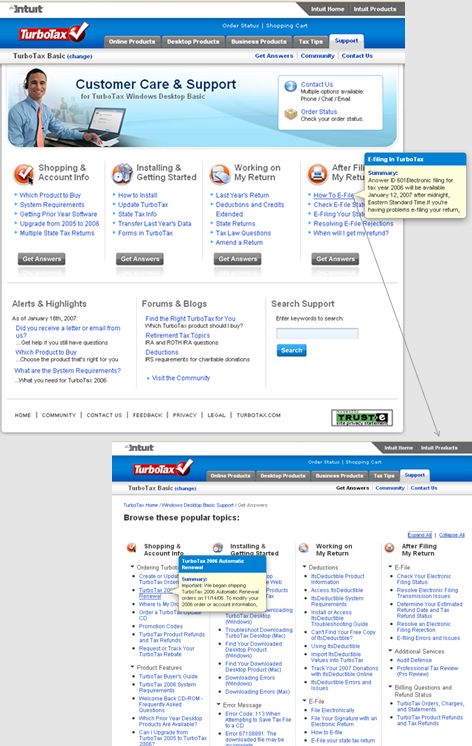

A Single Help Landing Page

For reasons of neglect or internal politics, many sites end up requiring customers to seek the information they need on many different pages—for example, Help, Top Questions, FAQ, Troubleshooting, Learning Center, or University. Offering dispersed collections of content without a single, well-integrated Help landing page often confuses customers about what kinds of Help are available and which content might actually support the need at hand. The best Web sites provide a single Help landing page where customers can obtain Help of all kinds:

- Help search

- common questions

- a Help index

- contact information, including email addresses, phone numbers, and chat and community links

One of the best examples of a single Help landing page is that for TurboTax, shown in Figure 5.

This page presents a clear process customers can easily follow to resolve their problems. Most options are clearly organized. However, customers must click a link to see a complete index of Help topics.

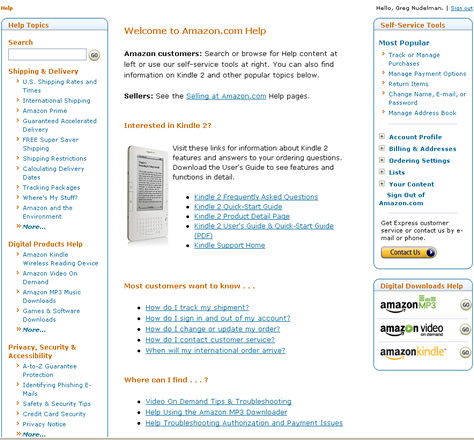

Amazon also provides an excellent Help landing page, shown in Figure 6. Note their relatively recent addition of a prominent Contact Us button. This is an improvement over their former Help page, which required customers to choose a category before seeing the Contact Us button.

Note that the Amazon Help landing page devotes a great deal of critical real estate to selling Kindle. While it may seem like a good idea to market the new device, the Help landing page is not the best place for promoting products. First, too much information about Kindle on the Help may naturally raise some questions about how many problems someone could expect when using the device. Second, people with real problems to solve might be annoyed by seeing so much distracting promotional content.

Navigation That Is Optimized for Browsing Rather Than Keyword Search

So where does search come into Help best practices? The truth is that simple keyword search is by far the weakest link in the Web site user assistance experience. Ray Bradbury famously wrote: “You need to know part of the answer in order to ask the right question.” In other words, a person seeking Help has to know the right terms to type into the search box, and often, they do not. Therefore, keyword search is often a customer’s last resort before contacting customer support.

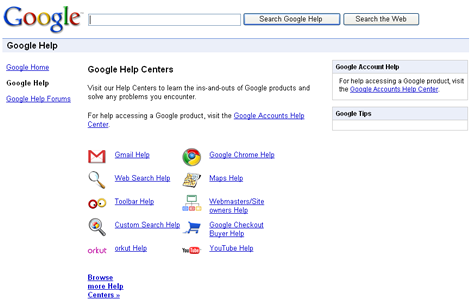

The good news is that, precisely because people are not familiar with a topic for which they are seeking Help, they are more likely to type in very general terms. Thus, designers should optimize the finding experience for general keywords and offer additional links to encourage exploration, making the experience far closer to browsing than to traditional keyword search. Even the simple search powerhouse Google opted for a friendlier browsable interface for their Help page, as shown in Figure 7.

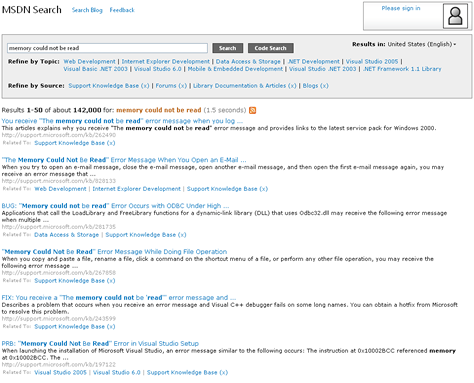

A specialized use case for searching Help is that of searching for the exact text of an error message when troubleshooting a problem. Advanced technical knowledge systems like Oracle MetaLink and the Microsoft Developer Network (MSDN) are optimized for this type of search. However, even for this use case, the user interface is closer to that for browsing than it is to traditional search. Notice that the MSDN Help search results in Figure 8 look very different from the kinds of search results we’ve examined previously in this column—the results that appear when customers search for specific items or content.

Gone are the prominent refinement controls, sort controls, and classification aspects from each row in the search results. Instead, each search result is considerably more prominent, with a text summary and multiple links to related items to encourage lateral exploration. Depending on the sophistication of an audience, such a page might also include some very general refinement controls for topic or content type. However, in the best systems, these filters are seldom prominent. The designer’s ultimate focus should be on providing a complete solution, including lots of links that let customers navigate laterally or even widen their search instead of constraining it further.

Complete Help Solutions Through Multiple Landing Pages

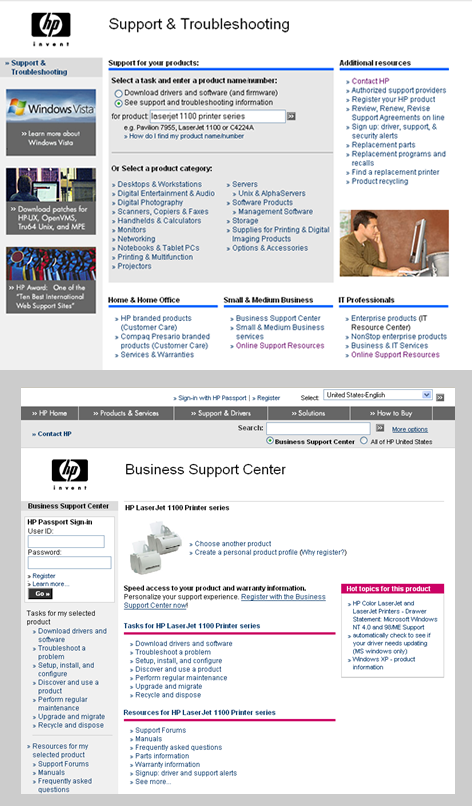

The best Help systems strive to provide a complete solution. On the HP Help site shown in Figure 9, the LaserJet Printer page is a landing page that provides all of the available Aspirin Help and Vitamin Help links for that printer, including user manuals, printer drivers, and setup guides. If just learning how to do something does not satisfy a customer, there are also lots of links to more sophisticated information that communicates the why of how, including links to support forums, upgrades, and parts.

Even though, in this case, a customer arrived at the HP LaserJet Help landing page by searching for Help, the user experience is much more that of a browsing user interface that gently guides customers to a complete Help solution for a product, offering links for further investigation.