1. Persuasive Design Doesn’t Address What We Think

Persuasive design focuses on people’s actions, or behavior, not their attitudes, or what they think. Why? The relationship between action and attitude is hard to measure. Despite that, most people—even academics—assume there is some relationship between what we think and what we do. In fact, there is a long-standing theory in persuasion circles called the theory of reasoned action. The evidence supporting it is considerable. [2] But, it will likely remain a theory, because it is difficult to prove entirely.

To me, the connection between what we think and what we do is like gravity. It is a long-held theory. As a theory, it makes sense and has supporting evidence. However, the exact nature of this complex relationship might be impossible to prove once and for all.

Here is my challenge. Although gravity is a theory, we still respect it. We plan for it. We don’t jump out of an airplane without a parachute because gravity is only a theory. A parachute like that shown in Figure 1 lets people defy gravity.

Persuasive design does not take attitude into account much in its planning, even though attitude is powerful. One famous example of attitude affecting action is the scientific taste test between the soft drinks Coke and Pepsi. (I mean the scientific one, not the tests for commercials.) When the taste test was blind, people chose Pepsi. When the taste test was not blind, people chose Coke. In other words, people’s attitude toward Coke was so strong, it drove people to choose Coke over their actual taste preference. [3] Brain scans showed that taste tests in which brands were visible actually triggered different brain activity than the blind taste tests did. That’s potent. Can we really afford to ignore it?

2. Persuasive Design Leaves Out Content

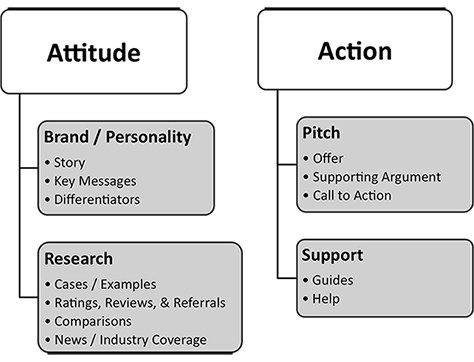

In my experience, content affects both what people think and what they do. Figure 2 shows a few examples.

When we include content in our planning for persuasive design, we gain greater opportunity to influence. Let’s look at an example from the health industry. CNN recently featured an exciting self-help treatment Kaiser Permanente launched to help people recover from an eating disorder. [4] Central to this treatment is content—a guide on how to overcome binge eating—and occasional coaching. As CNN described:

“Half the participants were assigned to treatment as usual. They received notifications about available nutritional services, medical treatments, healthy eating, and weight management programs.

“The other half were assigned to a self-guided program for 12 weeks, detailed in a book called Overcoming Binge Eating … and met individually with a health educator for eight sessions. Under the program, binge eaters kept food diaries and wrote what triggered their behaviors.”

Researchers found statistically significant results in favor of the self-help treatment. After a year, 63% of the patients in the self-help treatment had recovered from binge eating—compared to only 28% of the patients in the healthy eating program. The right content and coaching changed these people’s eating behavior. Are we letting content be all it can be in our persuasive designs?