However, if a page is well designed, high information density does not compromise either the reading experience or usability. If anything, a very compact screen design could enhance reading. Not only that, it might help in achieving greater user engagement.

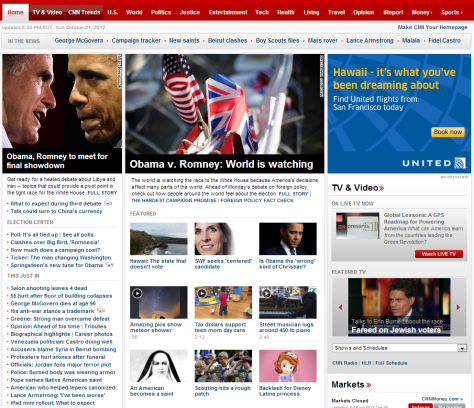

Let’s take a look at the home page of cnn.com, a page that obviously has relatively high information density. The text links on the left side of the page are all tightly spaced. There are many thumbnail images. The global navigation bar at the top seems to have too many items on it. However, many still find the page easy to read and fairly engaging. Why is that?

Taking a closer look, it’s easy to see that the page is very well organized. Key screen elements like the global navigation, the three-column page layout, the promotional areas highlighting top news stories, and the thumbnails in the middle of the page are all part of a well-organized design. Similar elements align with one another. For example, all of the hyperlinks at the left are left aligned, and there is no comingling of links with other types of content; images break up the text, helping users to scan the content. The horizontal layout of the global navigation bar and the three-column layout for the content follow common design patterns that are well understood by users. The visual design scheme features good contrast—red, black, and dark blue—across different types of content. The list goes on…

The message here is that—despite its high information density—this home page is easy to read and scan because it employs a few well-applied design guidelines. Before discussing these design guidelines, let’s look at some potential benefits of high information density.

Benefits of High Information Density

Placing more information within the available screen real estate has a few noteworthy benefits:

- leveraging limited screen real estate—An obvious benefit, of course, is that you can better leverage a Web page’s limited screen real estate. When you can fit more information on one page, users don’t need to scroll as much or click to go to another page as often.

- giving an experience of abundance—High information density can give the impression of abundance. When visiting ecommerce or news sites, users like to see lots of articles, images, and items for sale—just like when they’re browsing a newsstand or shopping at a mall. Making a page just a little bit crowded, while ensuring that it’s still well organized, makes visiting the site more engaging. During many usability sessions, I’ve observed that younger, more tech-savvy users are more likely to find pages that have high information density fun to read; while older, less tech-savvy users are more likely to become frustrated by this kind of information design.

- making it easier to find information—When looking for information on a Web page, many savvy users perform an intrapage search—typically, by pressing Ctrl + F—using their browser’s find capability to find keywords on the page. Having more information on the same page better supports this finding behavior. The more information there is on one page, the more likely that a user can find content using intrapage search.

- enhancing content discoverability—We all know that “out of sight, out of mind” is true for Web browsing. If a user doesn’t see certain content on a Web site’s home page, there’s great chance that user won’t explore the rest of the site to unearth that content. By placing all key information prominently on the home page—using excerpts, thumbnail images, and headlines—rather than hiding it within the layers of a site’s navigation system, you can help users to discover what a site has to offer and enable them to better appreciate the full breadth of the site’s content.