In this article, I’ll offer a few reasons why we should think twice before we choose to provide less content and functionality for mobile Web users.

Designing for Mobile Context

When designing for the mobile Web, there has always been a strong emphasis on context—the idea of being sensitive to where users might be and what they might be doing at the same time that they’re browsing your site. Is a user in line at the grocery store or on the living-room couch? Is a user connected to the Internet via Wi-Fi access, with fast page loads, or an infuriatingly weak Internet connection? Are both of the user’s hands holding the device in landscape orientation, or is the user using only the right thumb to navigate the interface in portrait mode? We have to think about all of this in addition to the inherent challenges that are associated with mobile, such as signal strength.

Being aware of best- and worst-case scenarios is always important when designing for mobile experiences. Unfortunately, along with all of the useful insights that our focus on mobile context has brought us, many have adopted some poorly founded theories have often resulted in the minification of mobile sites. Consequently, much of the content and functionality that you’d find on the desktop version of a Web site gets removed from the Web version, because of mythical assumption that they would require too much time, concentration, or data input to be useful on a mobile device.

Now, let’s look at three important reasons why we should not provide less content and functionality when designing for the mobile Web.

Reason 1: When Have We Not Designed with Short Attention Spans in Mind?

Context should always play an important role in mobile design. Of course, we need to factor in the user’s environment and the amount of time and attention the user can devote to using our Web site or application. But attention-span and focus issues aren’t specific to mobile. We’ve been thinking this way all along.

Perhaps without our realizing it, context is something that we pay attention to when designing all digital experiences. Let’s consider an example: When faced with designing a site that sells cars, we would never design with the assumption that a desktop user would have a large amount of uninterrupted time to focus on buying a car online—going through the process from start to finish. We realize that there are hundreds of outside factors that could stop or delay the completion of even such an important task. Perhaps the phone rings or the kids need help with homework, and the decision-making process gets disrupted. Or maybe, after lots of careful consideration, a user has chosen the right car, but by the time he figured out the best financing option and gotten financing approved, the car was already sold and the search starts all over again.

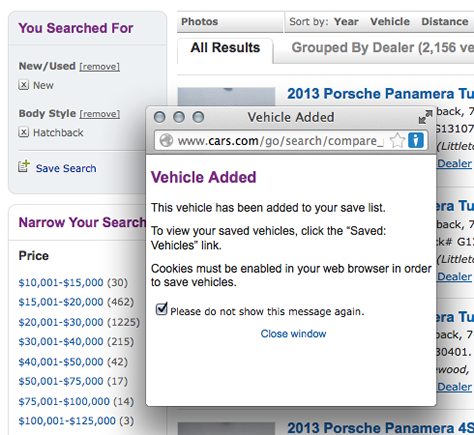

In consideration of such distractions and delays, we create features that let users save their search criteria or bookmark specific cars that they like, so they can view them at a later time. For example, as Figure 1 shows, cars.com lets users save searches and collect car listings in a personal list of Saved Vehicles for later reference.

Yet, despite all of the thousands of potential ways in which such a transaction could be interrupted, millions of cars get sold online every year. So why should we make the assumption that a user accessing the site on a phone or tablet would have a reduced attention span or more distractions, making the experience so different from that of desktop users that they wouldn’t want to buy a car online? We shouldn’t. Every 3 minutes in the UK, a vehicle gets purchased using the eBay mobile app; every 10 minutes in the US. There has been speculation that the benefits and delight that smartphones and tablets offer over the desktop experience will soon make mobile devices the dominant platform for the online shopping market. eBay’s researchPDF![]() states that 56% of shoppers who own smartphones believe that their smartphone will make their shopping experience more enjoyable.

states that 56% of shoppers who own smartphones believe that their smartphone will make their shopping experience more enjoyable.

We’ll continue to find that users are more and more willing to perform time-consuming and complex tasks on any device they have in front of them, as this quote from Brad Frost shows:

“Repeat after me: mobile users will do anything and everything desktop users will do, provided it’s presented in a usable way.”

Reason 2: The 50 Shades of Mobile Mystery

The problem with the term mobile is that, at best, its definition is outdated, and at worst, it’s indefinable. What does mobile mean exactly? Is a notebook computer not a mobile device when a person uses it at a desk, but a mobile device when someone carries it from meeting room to meeting room? How would you define context for the new 20-inch tablet, shown in Figure 2, which has a larger screen and is heaver than some standard notebook computers? The traditional definition of mobile, which has associated mobile devices—and therefore, mobile design guidelines—with smaller screen sizes is becoming more and more problematic as the lines between desktop, tablet, and phone screen sizes blur.

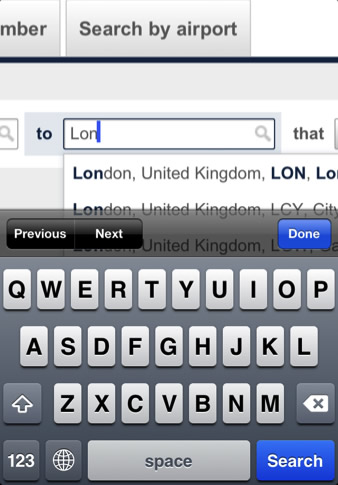

In addition to their having smaller screen sizes, we also traditionally define mobile devices as having no external keyboard, and thus, their not being people’s favorite devices for typing large amounts of text. But when you consider that consumers can now buy devices with optional keyboards that let them switch from tablet to notebook mode![]() in seconds, it’s clear that the line between which devices are typing friendly is getting blurred even further. Shown in Figure 3, the Windows 8 surface tablet has a pressure-sensitive cover that doubles as a full keyboard.

in seconds, it’s clear that the line between which devices are typing friendly is getting blurred even further. Shown in Figure 3, the Windows 8 surface tablet has a pressure-sensitive cover that doubles as a full keyboard.

Even typing on smaller touchscreens—and dare I mention the dreaded act of filling out forms— doesn’t carry such painful associations as it used to do. I’ve seen coworkers choose iPads over notebook computers to type notes in meetings at comparable speeds, and I’m probably not the only one who has marveled at how quickly some users can accurately crank out text messages on their touchscreen phones. Also, advances that make producing large amounts of text on mobile devices easier—such as external keyboards that plug into your phone or tablet, improvements in voice-recognition technology, and better swiping and autocorrecting functionality—require us to rethink our assumptions that typing is primarily the preserve of notebook computers and personal computers.

All of these ways in which the lines between mobile and non-mobile experiences are blurring together tell us that it is no longer acceptable for us to decide on behalf of users what they want to accomplish—simply because of their screen size or the lack of a traditional keyboard.

Reason 3: Not Mobile First, but Mobile Only

So far, I’ve talked about reasons not to remove content or functionality from mobile sites simply because mobile devices have smaller screen sizes and different ways of typing than a desktop computer—or because tasks are focus-intensive or complicated. However, debating what tasks users prefer to do on a personal computer versus a mobile device often misses a crucial point: A huge chunk of our users don’t even have a personal computer in the first place, so why are we removing content and functionality to which they’ll then never have access?

Here is some eye-opening data that demonstrates that we are part of a growing mobile-only world: There are an estimated![]() six billion cell phones in the world and only 1.2 billion computers, and the numbers will only become more skewed

six billion cell phones in the world and only 1.2 billion computers, and the numbers will only become more skewed![]() as personal-computer sales continue to drop worldwide while tablet sales soar. Recent technical improvements like cloud computing have reduced both time and bandwidth for the usage of Web browsers. Combined with lower costs for smartphones and tablets, and the increased attention that the UX community is giving to smaller browser-viewport widths, mobile devices have become attractive alternatives to their non-mobile counterparts. Lastly, in huge populations of the world such as China, India, Indonesia, and Africa, mobile Internet is often the only easy way to access the Internet, because a fixed-line Internet infrastructure is either too expensive or doesn’t exist at all.

as personal-computer sales continue to drop worldwide while tablet sales soar. Recent technical improvements like cloud computing have reduced both time and bandwidth for the usage of Web browsers. Combined with lower costs for smartphones and tablets, and the increased attention that the UX community is giving to smaller browser-viewport widths, mobile devices have become attractive alternatives to their non-mobile counterparts. Lastly, in huge populations of the world such as China, India, Indonesia, and Africa, mobile Internet is often the only easy way to access the Internet, because a fixed-line Internet infrastructure is either too expensive or doesn’t exist at all.