Effectiveness

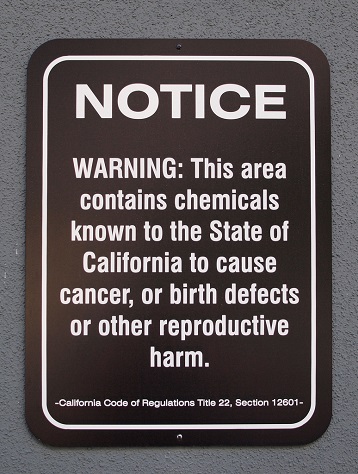

First, let’s consider the usability attribute effectiveness. Legal products are all too often ineffective. For example, Figure 1 shows a photograph of a warning sign that the California Health and Safety Code legally mandates in public buildings. Recently, I saw this warning sign on an airplane-boarding ramp as I exited my plane. What is its intended use? What goal does this message support?

Even though this warning sign does not indicate a specific response—as the ANSI Z535 standard for safety signs and labels requires—its purpose is presumably to inform people to take action to avoid the hazard of the aforementioned chemicals. [2] However, this avoidance behavior would not be realistic in that particular context. In this case, effectiveness might mean that travelers should not leave their planes. Such a response is not feasible. So how could anyone consider this warning to be usable in terms of its effectiveness when the context negates the implied response behavior?

Efficiency

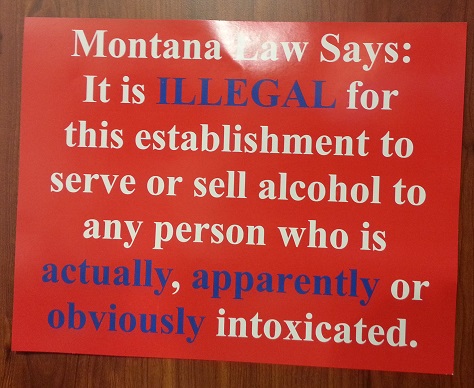

We can also consider the usability of legal products in terms of their efficiency. The example in Figure 2 shows a legally mandated sign that places serving alcohol in Montana must post. Its goal is to communicate that it is unlawful to serve additional alcohol to people who are already drunk. But how efficiently does this sign communicate that message to either servers or patrons?

The inefficiency of this legal message comes from the inclusion of multiple criteria that are ambiguous and redundant. What do apparently and obviously mean to an observer? Is there a legal distinction that most observers could make? And since it would be readily apparent that an obviously intoxicated person was also apparently intoxicated, why does this sign include both terms? Apparently intoxicated should be sufficient—and would help prevent debates about semantics between servers and patrons.

And how could a server determine a patron’s actual intoxication without the training or any equipment for collecting and testing breath or blood samples to determine alcohol levels? So, within the context of use, that stipulation is also unachievable.

Satisfaction

Let’s look at the usability of legal products in terms of satisfaction. Here, the focus is on people’s emotional response to products of the legal system—especially emotions in response to situations that require interactions with the legal system.

As an example, consider this clause from a legal document that is necessary for a woman to secure a donor egg in an effort to become pregnant and have a child:

“It is understood by all PARTIES that Ova(um) donation, including genetic material from the Ova(um), and ‘in vitro’ and/or ‘in utero’ fertilization are procedures within a new, unsettled, and uncharted area of the law, and no warranties have been or can be made as to the ultimate result, cost, liability, or obligation of the PARTIES, as a result of the conduct contemplated by this Agreement and/or that may ensue from any judicial, legislative, or administrative process as a result of the conduct contemplated herein or with respect to any arbitration/litigation necessary to establish any right of any of the PARTIES per this Agreement, including parental rights and/or financial obligations regarding any donated Ova(um), embryo, or Child(ren) born as a result of this Agreement.”

First, ignoring for a moment the inefficiency of the statement’s vocabulary and syntax, how does the sentiment of this statement in any way honor or support the positive and optimistic emotions of the person seeking to become a parent? On the contrary, the statement’s sentiment does nothing to increase satisfaction—rather, its explicit tone serves only to increase any doubt or stress in the reader. Clearly, this warning fails to consider the satisfaction of the intended reader—especially in the context of what should be a positive and reaffirming experience.