Book Specifications

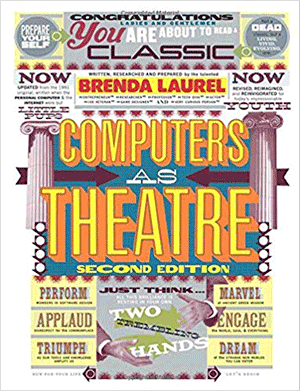

Title: Computers as Theatre

Author: Brenda Laurel

Formats: Paperback, Kindle

Publisher: Addison-Wesley Professional

Published: 2013, Second edition

Pages: 272

ISBN-10: 0321918622

ISBN-13: 978-0321918628

A Novel Approach

Frequently, the most insightful perspectives come from people outside a field. The typical UX book in my collection was written by someone in one of a limited number of professional roles. Authors might have a background in information science or product management. They might be an enlightened engineer or developer. Their experience might be heavy in visual design. They might have transitioned to a UX role, or they might simply have worked in User Experience for most of their career.

Although Brenda Laurel has been active in User Experience for decades, her education and perspective are unique in my collection, and her impact on the field of interaction design has been significant. With a PhD in theatre from Ohio State University and experience with stage performance, Laurel has served in faculty positions at a variety of colleges and universities. Plus, she worked at Atari in the early 1980s, as well as for a variety of technology and video-game development firms. Thus, she has a very rich background in video-game design. When one considers the interaction models and incentives for video games in relation to theatre, the connection seems obvious. This gives Laurel’s book Computers as Theatre its unique perspective.

I mentioned that people buy experiences, not products. This is perhaps most true of theatrical productions and video games. When we attend a performance, we are literally purchasing an experience that takes place over a period of time. The depth and mode of interaction can change, and a certain amount of improvisation is inherent in both theatrical performances and games.

Theatre includes concepts such as dynamic structure, a path that all stories typically take, including exposition, climax, and catharsis. However, we don’t usually discuss such things in experience design. There is also the idea of surprise—again, something UX designers don’t really talk about. Although the idea of delighting the user could come from surprise.

A particularly useful technique for understanding the satisfaction the user takes from an experience is Freytag’s triangle, a method of diagramming the dynamic structure of a story. In User Experience, we discuss user journeys, but I can imagine the use of Freytag’s triangle as a starting point for mapping out user experiences.

Much of the literature relating to User Experience focuses on one of just a few key topics: task engineering, users, research, information, or the design or usability of user interfaces. Many portray the experience the user has with a product or service as the outcome of design decisions relating to a user interface—as a metric that we can measure in negative or positive terms. This is somewhat incongruent given both the name of our field and the common mantra: people don’t buy products; they buy experiences.

Much of the literature relating to User Experience focuses on one of just a few key topics: task engineering, users, research, information, or the design or usability of user interfaces. Many portray the experience the user has with a product or service as the outcome of design decisions relating to a user interface—as a metric that we can measure in negative or positive terms. This is somewhat incongruent given both the name of our field and the common mantra: people don’t buy products; they buy experiences.