Start with the Roots: A Content Inventory

Before you can analyze your content, you must identify what content there is. For two useful perspectives on doing content inventories, see these essays:

- “Doing a Content Inventory (Or, a Mind-Numbingly Detailed Odyssey Through Your Web Site)”

[2]

[2] - “The Content Inventory Is Your Friend”

[3]

[3]

Ultimately, a content inventory results in a detailed spreadsheet that, at a minimum, lists the existing content.

Weed Out the ROT

A common method of analyzing content uses the ROT (Redundant, Outdated, Trivial) set of heuristics. Often an analysis using these heuristics is part of a broader content analysis, as the abovementioned essays note. This important analysis gets rid of the obviously bad content.

The problem? Many people end their content analyses there. For me, a ROT analysis is just the beginning. While it tells you what content is stale or woefully unimportant, it does not tell you what content is mediocre, inappropriate, inconsistent, or off brand. To reveal more useful insights about your content—and consequently, make better decisions about your content—you must take content analysis a step further.

Expand Your Tool Set, Then Work Away

Just as, to truly care for a garden, you need more than a weedeater, you need more than the ROT heuristics to analyze content effectively. In his Boxes and Arrows article “Content Analysis Heuristics,”![]() Fred Leise offers the following helpful heuristics [4], with a focus on information architecture:

Fred Leise offers the following helpful heuristics [4], with a focus on information architecture:

- collocation

- differentiation

- completeness

- information scent

- bounded horizons

- accessibility

- multiple access paths

- appropriate structure

- consistency

- audience relevance

- currency

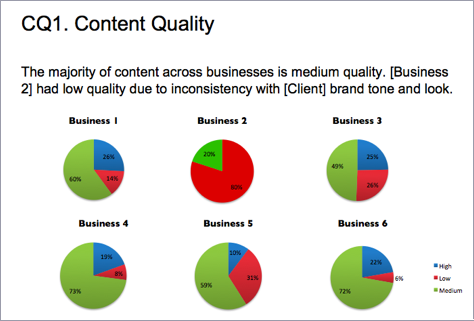

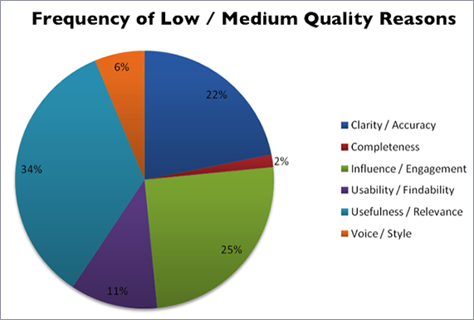

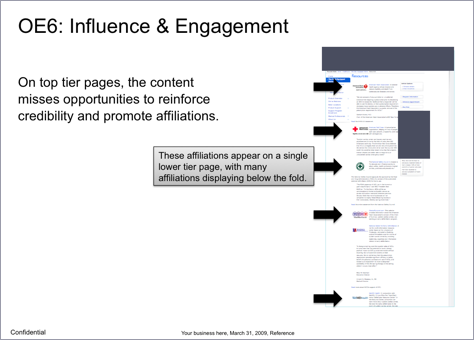

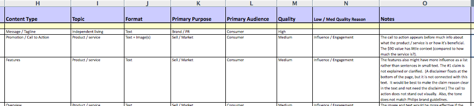

In a recent UXmatters column, “Toward Content Quality,” I shared some basic characteristics of content quality, with an eye toward turning them into heuristics: [5]

- usefulness and relevance

- clarity and accuracy

- completeness

- influence and engagement

- voice and style

- usability and findability

Other important, basic characteristics include some of those noted in the content inventory essays I mentioned earlier:

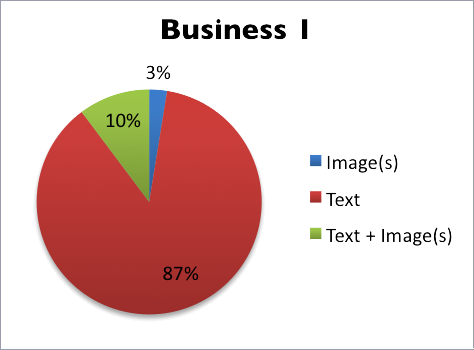

- type

- format—for example, text, PDF, or image

- intended audience

- business or user priorities

Plus, there are numeric ratings of quality or effectiveness you can use to judge whether content meets a heuristic.

Occasionally, you might want to add a characteristic to address a specific project issue, challenge, emphasis, or need. If there is a content characteristic you want to track or understand better, you need to include it in your content analysis.

Including every single heuristic or characteristic I just listed would make your content analysis extremely time consuming. You should select the combination of heuristics and characteristics that make the most sense for your project.

I recently decided to use a combination of some of these heuristics—taking some from each set—for a project that involved migrating and merging several disparate Web sites. After analyzing part of one Web site, I realized that a couple of my selections were not applicable or useful, so I dropped them.

When I finished, I found the results quite helpful. I’ll give you a glimpse of them in the next section.