Let’s consider the following scenario:

Deb is buying a camera online and needs a case to go with it. In which circumstance is she likely to buy a more expensive case?

- When a Web site recommends a case to her as she’s purchasing the camera

- When she realizes later that she needs a case

- Neither of the above

The correct answer is 1. If Deb is buying an expensive camera, the cost of the case seems minimal in comparison to the cost of the camera. A $30 case looks a lot cheaper next to a $600 camera than when a shopper compares it to other comparable camera cases.

In this column, I’ll describe how anchoring, ordering, framing, and loss aversion affect people’s decisions.

Anchoring and Ordering

One key aspect of the comparison process is something called anchoring. An anchor is a thing that serves as a reference point for our comparisons. In the previous example, the anchor is the $600 price of the camera. Because the price of the camera is the reference point, the $30 case seems like a good deal. If the $30 case were the reference point, the $600 camera would seem very expensive.

Another key aspect of the comparison process that influences people’s perception of value is ordering—how the items in a choice set are ordered. Together, these two key aspects of the comparison process—anchoring and ordering—play a significant role in how people determine value. Let’s look at another scenario:

You’re in charge of designing the wine list for a friend’s restaurant, and he wants his patrons to purchase primarily the more expensive wines. To achieve his goal, how would you arrange the wine listings?

- Alphabetically

- By price, least expensive first

- By price, most expensive first

- Randomly

The correct answer is 3. Why? Because when people read from the top of the page down, they encounter the most expensive wines first, so these set the anchor against which people compare all other wines. All wines in the list beyond the most expensive ones would appear to be a much better value.

If you instead ordered the wine list so the least expensive wines appeared first, those would become the anchor against which people would compare all other wines, and the wine list as a whole would seem more expensive. The ordering of items affects what becomes the anchor, or reference point, in people’s minds as they compare items.

Consultants who advise restaurants on how to design their menus have found that putting just a single high-priced item on the menu can increase the restaurant’s overall revenue. Why? Because, while people don’t typically order the most expensive option on the menu, they often do order the second most expensive item, which seems like a good deal in comparison to the highest-priced option. [1]

Implications for Design

As you can probably see, the design implications of anchoring and ordering are huge. Let’s look at an example of how you can apply these concepts:

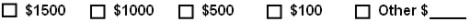

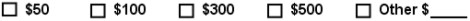

If, as the administrator of a local nonprofit, you’d like to increase the size of incoming donation amounts, how could you design the donation form to help achieve your objective? Let’s consider two possible designs for the donation form, shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Which ordering do you think would result in larger donations—and why?

There are two main differences between these examples: the ordering of the amounts and the size of the amounts. Each has an impact on the decision outcome. As I mentioned earlier, ordering the numbers so the largest amount appears first makes each amount thereafter seem like less money. It is, therefore, to your benefit to start with the largest amount.

But each example also uses different amounts. Why would this make a difference? Many people don’t know the right amount to donate. By listing some potential donation amounts, you set an anchor, or reference point.

When the amounts are larger, you’ll likely get bigger donations, right? Probably. But the outcome also depends on your audience. For instance, you may get a very different response if your audience consists of wealthy people versus college students. Your anchor points must be realistic for your target audience. Therefore, to use the concepts of anchoring and ordering effectively, you need to know your audience.

Framing Decisions

We’ve seen how anchoring and ordering influence the perception of value. The language that we use to frame a decision process also influences people’s perceptions greatly. To illustrate, let’s consider an example:

What if you encountered the following options?

- A pound of meat that is 90% lean

- A pound of meat that is 10% fat

Which would you prefer?

Even though these are just two different ways of saying exactly the same thing, you’d probably prefer option 1. Why? Because lean meat is better than fatty meat. The description, or frame, in which we present a decision highlights different attributes—lean versus fat—to which we draw the decision maker’s attention.

Now, this may seem like a simple example, but the concept of framing plays out in a myriad of ways in our daily lives, influencing our decisions in ways that we are largely unaware of. For example:

If you were a physician advising a patient on a form of treatment, you could frame the decision about whether to employ that treatment in either of the following ways:

- This treatment has a 90% chance of saving your life.

- This treatment has a 10% chance of failure, resulting in death.

People would respond differently to these two ways of framing the decision, even though both statements are essentially equivalent. Why is this so? Each of the two options presents a different perspective on the decision outcome. As a decision maker considers the outcome of a decision, we can draw his attention to either a positive outcome or a negative outcome—a gain or a loss.