In 2009, Google conducted some research, taking a survey to New York’s Times Square and asking a random sample of people some specifically worded questions to determine whether they knew what a Web browser was. Only 8% responded correctly.![]()

The introduction of a search box into the Mozilla Firefox Web browser user interface greatly improved the user experience by making search easier. The engine behind that user interface lets users choose one of a number of search providers as the default. More recently, many Web browsers have merged the functions of the address bar and search box in an omnibox.

However, the business of search faced a significant problem: there is a statistically significant group of people who don’t know the difference between products and the Web browser they use to access them.

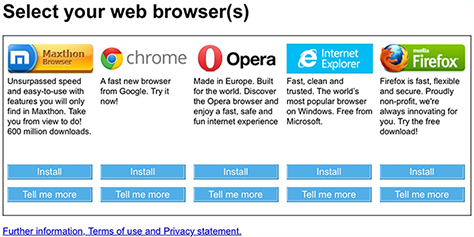

Ultimately, a computer or device operating system is the last touchpoint between users and their access to tools. When an operating system (OS) offers a default Web browser that is embedded into the system, how many of the large population of users will be aware that there are options beyond the default Web browser? How easy do OS vendors make it to install and use other software—especially applications from competitors?

Defaults and the Power of Inertia

Many users never change the default settings![]() on their computers. This must mean most people generally trust that the products that come bundled with their computers and other devices are good enough for their needs, and they often remain incurious about other options.

on their computers. This must mean most people generally trust that the products that come bundled with their computers and other devices are good enough for their needs, and they often remain incurious about other options.

The book Nudge,![]() by Cass Sunstein and Richard Thaler, discusses research into behavioral psychology, decision making, choice architecture, and the power of defaults that explains this phenomenon. It also challenges leaders in public policy and the private sector to ensure that people in the powerful role of choice architect—who subtly influence and steer people’s decisions—are doing so in an ethical and sensible way.

by Cass Sunstein and Richard Thaler, discusses research into behavioral psychology, decision making, choice architecture, and the power of defaults that explains this phenomenon. It also challenges leaders in public policy and the private sector to ensure that people in the powerful role of choice architect—who subtly influence and steer people’s decisions—are doing so in an ethical and sensible way.

The mobile app store has seemingly helped to offset the fear of change that casual computer users may experience when downloading or installing software that could potentially be harmful to their user experience. They may perceive harm from

- a reduction in current-state familiarity

- a more complex solution that is less easy to use

- the complexity of recovering the state of their system prior to installing something that could break a satisfactory status quo

- being deceived and installing something that exploits their ignorance or trust

- a lack of faith in crowd-sourced information from experiencing that a collective can miss important details

What often happens in such situations is that kind, more technically advanced users share their knowledge about other product options with novices and explain their benefits to them. However, those experts may be biased toward whatever applications they’re most comfortable with, potentially making them evangelists who steer novice users toward their own preferred products, regardless of whether they’re aware of doing so.