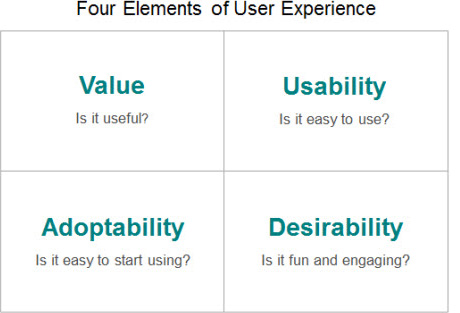

In attempting to achieve conceptual simplicity, I’ve reduced the many aspects of user experience to the four elements that I believe are the most fundamental. It’s possible to treat additional aspects of user experience as subcategories of these elements—for example, credibility, accessibility, and findability, from Peter Morville’s user experience honeycomb.

Usability—Is It Easy to Complete Tasks?

While people sometimes use the term usability to refer to all elements relating to user experience, it should more appropriately be viewed as just a subset of user experience.

Usability is about how easily users can complete their intended tasks using a product. There are many types of usability issues that hinder users’ ability to complete the tasks that they intend to perform. Let’s look at some examples.

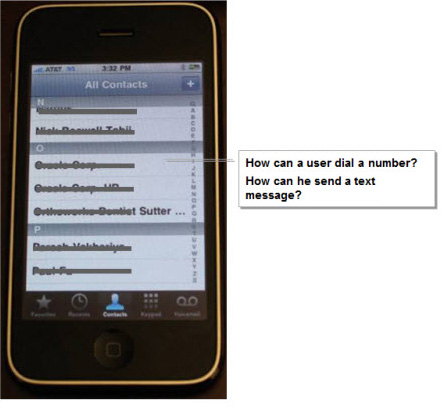

A person takes out his iPhone because he wants to dial a phone number to call a person who’s not in his contacts, so he has to input the number. He taps Phone at the bottom of the screen. Easy. What’s next? Well, there is no keypad on the screen. Nor is there a field into which he can enter the number. In interaction design terms, there is a lack of any call to action, affordance, or contextual cue. So, he spends some time inspecting the screen, and after about 30 seconds, he discovers the Keypad button at the bottom, shown in Figure 2.?He’s solved the problem, but discovering how to enter a phone number, one of the primary functions of a phone, should not take that along! This is a usability problem.

Here’s another example. Do you recall your first experience using your company’s intranet to do things like getting new office supplies, submitting an expense report, managing your career development, or taking a look at your paycheck? Were you able to use the intranet effectively without asking the help desk or your colleagues for help? I doubt it. Many intranet sites have really, really bad usability—so bad that you could probably never figure out how to do some tasks on your own.

These just a couple of examples that demonstrate the frustrations of performing tasks using software that has usability issues—as most applications do.

Usability is not about user intention, user engagement, or visual appeal—the other elements in my user experience framework. But usability does encompass all of the UX elements relating to ease of use. Things like learnability; content discoverability, findability, and readability; and the ease with which users can recognize information and affordances all fall into this category.

Usability, in itself, is a vast topic, and an entire generation of human/computer-interaction professionals have devoted their careers to advancing the field and improving digital-product user experiences. However, user experience goes far beyond users’ being able to complete their tasks, learn about new features, and find their way around a Web site. In fact, some other aspects of user experience are probably more important when it comes to driving business success.

Value—Does a Product Provide Value to Users?

While usability is an important aspect of product design, it is certainly not the most critical aspect of user experience when it comes to driving business success. There are many products that have good usability, but do not enjoy success in the marketplace. For example, traditional mobile phones are giving way to smartphones, even though many phones are very easy to use. Why? Because mobile phones do not provide the value to users that smartphones do. Consumers want the ability to surf the Web, use instant messaging, play games, and use GPS services on their mobile devices. Here, we are talking about the value aspect of user experience.

What drives a product’s value to users? Alignment between product features and user needs. If a product’s features are designed in such way that they support user needs, users will consider the product valuable. User needs encompass more than just their explicit needs—things that users know they want. They also include users’ implicit needs—things that users don't express as needs. Apple products like iPhone and iPad are excellent examples of satisfying implicit needs. In meeting users’ unexpressed needs, they are not only easy-to-use products, but also devices that add much value to users’ daily lives.

Perceived value is closely related to the other elements of user experience such as usability and desirability, but the key drivers of value are a product’s functionality and features. Value forms the cornerstone of a good user experience. A product that does not add value by fulfilling user needs does not provide a meaningful user experience—regardless of how well it might be designed.

Adoptability—Will People Start Using the Product?

The Yahoo! Web browser toolbar, shown in Figure 3, might be both easy to use and valuable to a typical Internet user, but if users don’t install it, all of the product’s good features become irrelevant. This is the adoptability element of user experience.

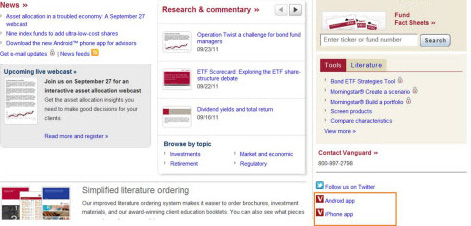

Let’s look at some other examples of adoptability issues. When companies launch their iPhone apps, they typically embed links to the apps on their desktop Web sites. However, this is a very problematic design decision: a user is visiting such a Web site on a computer, so how can she click the link to the application and download it to her iPhone? The Vanguard financial-advisor site, shown in Figure 4, exhibits this problem.

The right way to introduce Vanguard’s iPhone app would be to place a link to it on their mobile site, which shows up by default on the iPhone. However, when I took a look, I found that their mobile site doesn’t provide such a link. So, here’s a failure of adoptability: users simply don’t have a straightforward way of downloading the Vanguard iPhone app. So they need to go to the Apple iTunes store, search for the keyword Vanguard, select the right Vanguard iPhone app, and install it—not the most spontaneous way for users to get on board.

Based on the above examples, it’s clear that adoptability has a lot to do with the design of workflows. In addition, adoptability depends on things like credibility and brand perception. Content that does not look authentic or that is associated with a weak brand will have problems drawing users.

Adoptability is very closely related to usability. To improve adoptability, UX professionals employ robust usability techniques to ensure that they design a product’s workflows to support users’ natural ways of discovering its features. However, these two elements are also fundamentally different. Adoptability relates to users’ buying, downloading, installing, and starting to use a product. In other words, adoptability is about that stage when a user has not yet used a product, while usability becomes most relevant once a user has begun using a product. By making this distinction, I hope to call out an often neglected aspect of UX strategy: providing easy access to a product.

Adoptability is also clearly different from value. Even if a product brings great value to users, they still might not choose to use it because of difficulties relating to access and installation, as I’ve illustrated in my earlier examples. In other words, adoptability relates to obtaining access to a product, while value relates to a product’s features and content. To improve adoptability, a product team must consider the natural context in which a user first gets exposed to their product and how it impacts the design of the installation flow.

At first glance, adoptability seems to relate to product marketing—both are about promoting product usage. However, unlike traditional marketing, which focuses on marketing campaigns, Web promos, marketing email messages, and so on, adoptability is a user experience element that you should consider as an integral component of a product’s design.