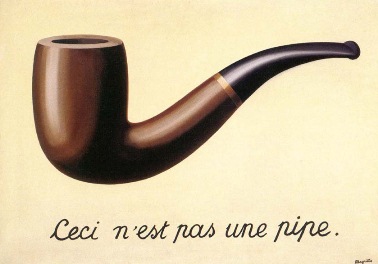

I thought about what they said and came to the conclusion that they were right. In fact, there is no such thing as UX strategy. Just because there is a UX Strategy group on LinkedIn with over 2500 members and a UX strategy conference in the planning stages, that doesn’t make UX strategy real in the same way that other disciplines and roles—for example, information architecture—are real.

Making UX Strategy Real

But I remember when information architecture wasn’t real either—outside a few early visionary agencies like Clement Mok’s Studio Archetype. It took thousands of projects and millions of project dollars before client partners began to say, “It’s critical that we staff an expert information architect on this project.” UX strategy is in a similar phase now: a few visionaries, a few experts, some digital buzz. It is still very much a practice and a role whose impact we can recognize more in its absence than in its presence—much like information architecture in the 1990’s, when the lack of an information architect could cause the design of a complex site or application to become convoluted, interactive spaghetti.

It is the absence of UX strategy that is, in fact, making it real. The absence of UX strategy in a range of situations is driving UX professionals to bring it into reality by embracing it as our professional focus, producing new work products, and establishing new consulting practices. Agencies like Foolproof in the UK and Retail UX in the USA are pushing hard to make it real, but it’s still relatively rare for organizations to give UX strategy an established place in their budget, resourcing, and project plans.

Sound like nonsense? Consider the following scenarios, which represent real situations interactive agencies and design teams all over the world have encountered.

User Experience Design by Committee

Large organizations are seemingly held together by meetings. Meetings in the morning, at midday, in the afternoon, and in the evening. Meetings during meal times. Meetings within meetings. So, it’s not strange that such organizations would want to meet to determine the design direction for a site, application, or product. The result is design by committee.

In such scenarios, organizations feel the absence of UX strategy when one of the committee members gets up his courage and presents best-in-class design work from competitors alongside what the committee has produced to deliver the same feature set. How could the competition have advanced so far while we’ve stayed within our safe boundaries—where we’ve been for years? Hasn’t anyone been keeping track of where the competition was heading?

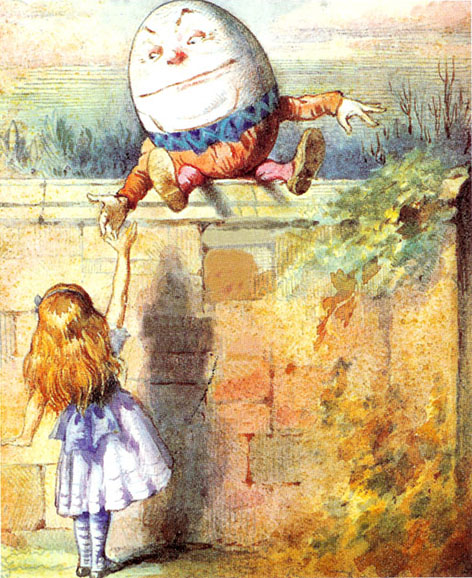

User Experience Design by Executive Fiat

Similar to design by committee is the situation in which a design team’s work gets approved or rejected by a single executive. Consider a hypothetical situation with an executive that I’ll call Brooke. Team members ask, “Has Brooke seen this yet?” “Does Brooke know?” “What did Brooke say?” Brooke represents just one of a thousand faces, but the result is the same. A single, absolute gating of all design ideas. The benefit of such an arrangement is that there is no ambiguity about how decisions will get made or who will make them. The downside is that design can never go beyond Brooke’s vision. Seem far-fetched? Not to those of us who have lived it.

Team members in such a scenario feel the absence of UX strategy when they question how all decisions can possibly rest with one person. Doesn’t someone in leadership realize Brooke’s limitations? Can’t someone prove to them that the work we are producing is less than it could be? Can’t someone demonstrate that we could be accomplishing a lot more than we are?

User Experience Design as Incremental Improvement

A/B testing is both a boon and a curse. It’s a boon because it gives a very clear indication of which of two designs has, for example, a higher conversion rate on a live Web site. It is a curse because the new designs that get tested must necessarily be very similar to the design for the current site. If it isn’t, the team won’t be able to discern which of the differences caused an effect. This is, of course, where multivariate testing comes in. But even in multivariate testing, there has to be a clearly defined, limited set of design differences in order to draw definitive conclusions about what is causing the results.

A business strategist in such a scenario is feeling the absence of UX strategy when he asks about the potential market value of solutions that are vastly different from what is currently in place. (This actually happened on a project in which I was involved.) “Maybe it’s not a question of improving what we have,” she said,“ but of thinking of something new that meets needs our customers aren’t yet aware a UX design could meet.” Foundational UX research that explores new behaviors or new technologies is a completely different—and much more unpredictable—sort of investigation than testing fully formed design solutions.