A Very Brief Introduction to Personas

Personas are archetypal representations of audience segments, or user types, which describe user characteristics that lead to different collections of needs and behaviors. We build up each archetype where the characteristics of users overlap.

According to Alan Cooper, author of About Face 3.0 with Robert Riemann and David Cronin, “The persona is a powerful, multipurpose design tool that helps overcome several problems that currently plague the development of digital products. Personas help designers:

- Determine what a product should do and how it should behave.

- Communicate with stakeholders, developers, and other designers.

- Build consensus and commitment to the design.

- Measure the design’s effectiveness.

- Contribute to other product-related efforts such as marketing and sales plans.”

But where do we start looking for the data we need to build up these useful archetypes.

Research Methods

Several research methods can provide data upon which we can build user archetypes, including

- surveys

- ethnographic research

- interviews

- contextual inquiries

- Web analytics

Surveys

Surveys provide a combination of quantitative and qualitative data, depending on how we structure the questions. Their purpose is usually to generate a relatively large data set in an efficient manner. Compared to other methods of research, a survey is a fairly inexpensive activity to undertake. Surveys are also quite flexible—in that you can ask a wide variety of questions and define the formats of the responses you’d like to see. (Good survey questions provide a clear indication to respondents of the type of information desired.)

As with all research techniques, surveys have their downsides. The quality of the data can be patchy, especially when gathering responses electronically. Respondents are more likely to skip questions or provide only superficial, brusque, or incomplete answers. This is particularly true when respondents perceive questions as touching on personal topics.

Survey responses can also be effectively meaningless—for example, when a respondent doesn't understand a question. Without a researcher on hand to clarify the intent of questions, responses may miss the point, rendering them useless. Good survey questions can mitigate this problem, but cannot remove it entirely.

And of course, we need to analyze the larger volume of data and all the responses to the multiple questions we’ve asked. This can require the use of specialized skills and software, raising the required level of effort. Since our aim is to generate audience segments, we need to perform multivariate analysis on the data, employing techniques like clustering, principal components, and factorial analysis. It simply isn't enough to analyze each question independently and fall for the ‘average user fallacy’.

We also need to recognize that people are generally fairly poor at reporting reality in surveys, particularly when we’re asking them to report on an event that occurred in the past. Questions such as On average, how often do you visit X per week? are bound to result in inaccurate responses. Respondents will offer exceptions, bad estimates, and sometimes make up responses based on their vague recollections. To provide balance to our data, we need other research sources with which to cross-reference survey data.

Ethnographic Research

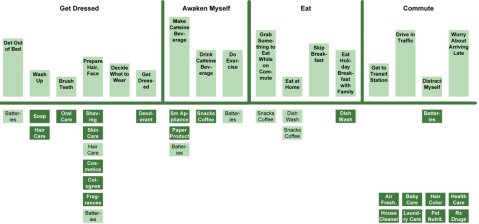

Ethnographic research includes a broad range of contextual, observational research techniques and offers a range of benefits to UX researchers. We can learn something about the context of use for a product or service we’re designing, including the environment, time constraints, and interruptions and distractions people face when interacting with our designs.

We also get to see what people actually do rather than what they say they do, overcoming a common problem with surveys and interviews. We can see the complex, unvarnished reality instead of the sanitized and tidy version people tend to portray in response to a question. And we can gain an understanding of both mundane, day-to-day activities and the more rare, extreme cases. Imagine the difference in the insights we can gain from a series of survey questions asking a theater nurse to describe her job, versus what we would learn by spending a few days following her around and observing her work.

On the downside, ethnographic studies can be time and resource intensive. Such studies require researchers to be on site with participants for an extended period of time—for days, weeks, or sometimes even months. And while the data we collect during such studies is very rich, it can also tend toward the messy, complicating the analysis process. However, ethnographic studies provide an excellent source of real insights into the audience for a product or service we’re designing.

Interviews

In terms of research styles, asking potential or current audience members a series of open or closed questions sits partway between surveys and ethnographic studies. Interviews are a good method for gaining insights into users’ opinions, thoughts, and ideas.

In ethnographic studies, researchers look at the actions and behaviors of participants. They interpret what they see rather then asking participants. The interview format allows some flexibility for researchers to explore ideas and motivations that are not accessible to an observer.

Contextual Inquiries

The contextual inquiry research technique combines observation with interview-style question and response. The aim of questions is typically to get participants to explain their actions and, in some cases, we ask participants to speak aloud, telling us whatever they are thinking as they work through a task or activity.

The downsides to contextual inquiry are similar to, but less severe than those of ethnographic studies. To gain sufficient insight, it is necessary to invest time in both the observation and analysis tasks, which represent a substantial effort.