The ability to communicate seems obvious, because we encounter many forms of communication daily. We read the news, shop online, review our bills, write or comment on a blog, and more. But ask anyone what communication is and how to make it better, and you’ll hear some hemming and hawing. We’re so close to it, we can’t describe it—it’s tacit knowledge. And, ironically, I think it’s even more tacit to UX professionals. I’ve done my share of hemming and hawing on this subject, so I don’t claim to have the perfect definition. But I find three perspectives provide a useful start:

- A model

- A theoretical view

- An experience strategy

The Basic Model: Quiet the Noise

You might have seen some incarnation or other of the classic Shannon-Weaver communication model, which has its basis in information theory. [1] This model describes how noise, or interference, is a major way in which we lose communications, as shown in Figure 1.

Shannon and Weaver focused on the technical aspects of communications—how to get information from one system to another without degrading the message. But their basic model is useful even when thinking about the social and psychological aspects of communication. Here’s a variation on their model that highlights three types of noise we encounter today—technical noise, semantic noise, and organizational noise, as shown in Figure 2.

Technical Noise

Technical noise occurs within and can disrupt a communications channel. An example of technical noise is Outlook’s blocking the images in an HTML marketing email message. The customer doesn’t receive the message in its intended form, so literally doesn’t get the message. UX professionals can help solve this problem by developing best practices for email formatting—for example, ensuring headlines, calls to action, and key messages are not in images. Usability and accessibility standards largely address the problem of technical noise. I like to think of this as optimizing a channel of communication for use.

For large Web sites and multichannel communications, a major source of technical noise is content and document management technologies. These technologies are critical, but we spend too much time figuring out how to get the system to deliver the information and not enough time thinking about what information is useful and how it should communicate to customers. Even Forrester Research acknowledges this problem, calling for less focus on managing content and more focus on the customer’s use of content. [2]

The mobile channel, IVR, kiosks, and other interactive communications channels have technical noise considerations worthy of their own articles. Suffice it to say that UX professionals must be involved in addressing the usability and accessibility issues for these channels.

Semantic Noise

Semantic noise is a problem with language or interpretation. An example of semantic, or language, noise is a company’s using different terms for the same concept in various communications. For instance, a wireless company might refer to a mobile phone as a phone on the Web site, but a device on the tech support IVR. UX professionals can help identify what term is most appropriate for customers and recommend its consistent use.

A more extreme example of semantic noise occurs when a customer calls a company and reaches a representative who isn’t fluent in the customer’s language. Perhaps the customer’s idiomatic phrasings confuse the representative, and the representative’s non-idiomatic phrasings sound awkward to the customer. A less extreme example is when a call center representative uses jargon that, to the customer, could just as well be Greek—for example, saying power on when meaning to turn on a mobile phone. UX professionals can help solve these kinds of communication challenges. We expect call center representatives to diagnose and solve customer problems in minutes, so they must follow the steps through which their computer applications guide them. They must also rely heavily on product, service, and other content on the corporate intranet and Web site—usually reading it out loud. So designing call center applications that provide the right guidance and intranet content that uses customer-friendly terminology can go a long way.

Let’s not forget interpretive semantic noise, which occurs when the customer receives the intended message in the right language, but still doesn’t get it. One example is organizing information on a Web site from the company or organization’s perspective instead of the customer’s perspective. Thankfully, information architecture can correct this problem on Web sites. But what about on other channels? When the prompts on the main menu of a bank’s IVR are a list of its internal departments rather than the tasks customers want to complete, customers are in trouble. Interpretation of the prompts on an IVR is especially noisy. There are no visuals, just spoken words. My experience designing and testing IVRs for the wireless industry has made it clear that, if the wording of menu options does not have the right balance of concision and descriptive detail, customers cannot interpret them well enough to choose the right option.

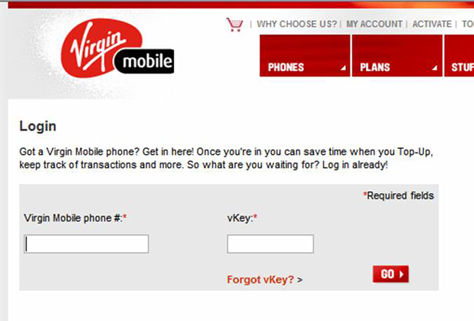

Other examples of interpretive noise lie in the context, tone, examples, and other such subtleties. The informal, irreverently fun tone on the Virgin Mobile Web site—even on its login page, shown in Figure 3—likely is a hit with the targeted customer segment. However, this tone wouldn’t work on a medical Web site designed for elderly people.

In the site’s Help, shown in Figure 4, a simile comparing auto-pay service with valet service might confuse customers if the target customers are not familiar with valet services.

Organizational Noise

If organizational silos were sound, they’d be deafening thunder claps. Many companies have channel silos that operate independently and even compete against each other—for example, store sales versus Web sales versus phone sales. A siloed structure means no one is really responsible for or able to implement a cross-channel communication experience, involving message coordination, content consistency and relevancy, and the optimization of messages for channels. Employees working in a channel try to keep customers using only their channel—when, in reality, customers might prefer to use multiple channels.

Peter Merholz has talked about encountering these types of silos in the financial services industry. [3] I experienced such silos at Cingular Wireless, where I watched customers looking puzzled as if their amount due were different on their paper bill, their online bill, and the IVR. (If there’s any communication that customers check via multiple channels, it’s the amount due.) Focusing on a strategy that unites channels can help overcome these silos. I was part of the company’s UX group, and we focused on customer self-service, not a solitary channel. With the help of an executive advocate, we made strides in overcoming the challenges of channel silos. We completed work on the Web site, the IVR, store kiosks, store collateral, welcome collateral—sent with all phone shipments—call center applications, mobile applications, and more. The pay off? Boosts in customer satisfaction and reduced customer service costs.

Many leading retailers get the importance of channel integration. Circuit City emphasizes its three ways to buy—in the store, on the Web, and on the phone, as shown in Figure 5. Circuit City, REI, Best Buy, and others also let customers order online, then pick up their purchases from a nearby store.

For some products, Amazon.com offers to call customers to help answer questions about the products, as shown in Figure 6. I look forward to such retail channel integrations influencing service providers, too.

Later Communication Models: It Goes Both Ways

People have praised the original Shannon-Weaver model for its simplicity, but also criticized it for not reflecting the complexity and interactivity of human-to-human communication. I find three goals of later communication models helpful in addressing its deficiencies:

- Emphasizing the interaction between senders and receivers, or two-way communication

- Demonstrating how, when the receiver communicates back to the original sender, the same opportunities for noise occur

- Focusing more on interpretation

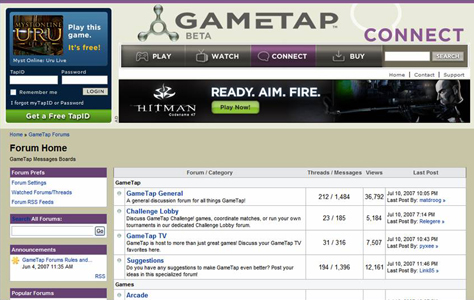

Today, on the Web alone, customers have plenty of opportunities to provide feedback to and about companies and their products—through email, customer reviews, blogs, discussion forums, and customer ratings. Companies need to pay attention to what customers are saying to them and about them to enable better communication with them in the future. Companies also need to facilitate an ongoing connection with their customers.