The Background Story

The term co-design—now in common use in both design and research contexts—derives from the work of Elizabeth Sanders and others on participatory design and co-creation. Sanders defines co-design as “collective creativity as it is applied across the whole span of a design process” [1] and has developed many different tools and methods to enable co-design in different product development settings.

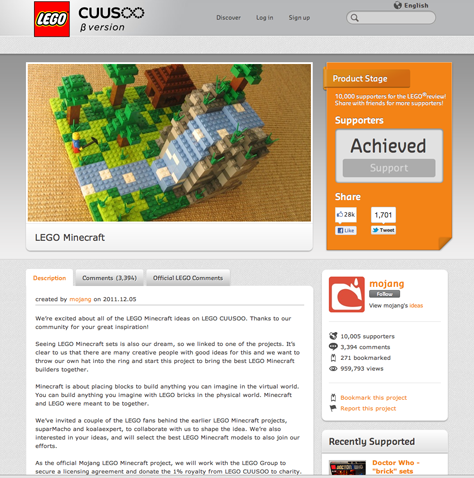

Specifically, in the area of co-designing with children, the work of Alison Druin and others has provided many frameworks and methods that allow you to work with children as partners during a design process. In Druin’s paper, “The Role of Children in the Design of New Technology,” [2] she explains the different roles in which you can involve children in a product development process, using the diagram shown in Figure 1.

At different stages in a product development cycle, co-designing with children may include some combination of all of these roles. However, this article focuses mainly on including children in the design process as informants and design partners.

The Research Methods

Next, I’ll discuss some co-design methods that you can use with children at different stages of the product design process. The appropriate methods may vary depending on the purpose of your research. My goal here is to give you an idea of what methods to use to meet the specific needs of the researchers and designers on your UX team. (This is not an exhaustive list of research methods. Explaining each method in depth would require a separate column.)

Methods for Developing Self-Awareness

Sanders recommends that, before you conduct any co-design sessions, you should do a series of self-awareness exercises that allow participants to reflect on everyday activities that they would normally take for granted. The results of these exercises can serve either as inspiration for an on-site research session or as a guide to digging deeper into areas that the design team considers to have more innovation potential.

With children between the ages of 7 and 11 years of age, workbooks or journals that they can take home and fill out work well. For older children, more recent experiments include using online research tools and storytelling using videos or pictures that children have created.

Mobile diary studies that portray a-day-in-the-life data are an effective tool when conducting research with teenagers or the parents of young children who are not yet able to go through a research exercise on their own.

While doing such preparatory research exercises is not always possible, because of time or budget constraints, they provide a valuable opportunity both for the design team to learn more about the kids and their world before starting the co-designing process and for the kids to start preparing for the on-site creative exercises.

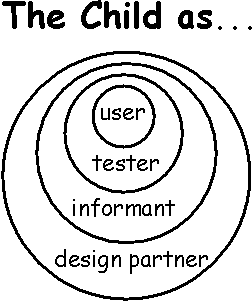

If the children with whom you are working have been using a product for a long time and are deeply passionate about it, you can usually bypass these exercises. Chances are that these children will already be full of ideas about how to improve the product by the time you talk to them and eager to share them with you, so they won’t need to do any warm-up research activities at home.

Methods for On-site Research

All co-design sessions require the use of stimuli or a toolkit that facilitates discussion and spurs creative thinking. When a design research team is working with children, the creation of these toolkits requires secondary research into psychological and developmental guidelines for children in various age groups, as well as images and words that children understand and can relate to easily. Plus, you should do a pilot test with kids to assess how well your toolkit is working.

If you are conducting user research sessions at frequent intervals throughout a product development cycle, you’ll be able to refine your toolkit as you go through the process and become better acquainted with young participants.

The user research methods that I’ve presented in this column are generally appropriate for children 6 years of age or older, with the exception of the mixing-ideas methods.

Discovering Emotions, Feelings, and Dreams

Discovering emotions, values, ideas, dreams, desires, and ideal situations is a crucial part of user research during the early stages of the design process and usually requires generative research methods. There are numerous ways of doing generative research, each of which presents different challenges when working with children, as follows:

- collages—You can get children to create collages to elicit discussion of the intangible—feelings and emotions. Children typically create collages by choosing images from a large set of visual stimuli.

- context mapping—This method lets you understand a child’s world—what she values or likes and how she perceives different aspects of her life, a brand, a system, or an experience. As when creating a context map with adults, a representation of the child is at the center of the map. Layers start to form as the child first represents what she considers most important or closest to her. Variations of this approach include doing context mapping as a game, using specific shapes or colors.

- storytelling—You can elicit storytelling in a number of ways when working with children. Storyboards, simple drawings, modeling, image cards, role playing, fantasy games, and mixed-materials toolkits can help you to understand future experience journeys and ideal processes as stories.

Recently, I have used a variation on these approaches, involving a rapid visualizer or illustrator in the sessions who attempts to represent what the children are imagining. In this case, the children act as creative directors, guiding the illustrator in his creative effort.